Posted on 6 November 2020 by Juan Ocampo (Department of Business Administration, Lina Van Dooren (Malmö Academy of Music) and Soo-hyun Lee (Faculty of Law).

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Agenda 2030 Graduate School or Lund University. The present document is being issued without formal editing.

Introduction

Research regarding innovation and team creativity points to group composition, environment, and participant skills. With a common interest in studying and researching sustainable development, the Agenda 2030 Graduate School is composed of a group with diverse personal and professional backgrounds, thus making it an appropriate environment for innovation and creativity. Sarah Harvey argues that “(…) group creativity occurs because the space that exists between members’ different perspectives offers the opportunity for a new framework to develop that connects them[1]”. Inspired by the creative synthesis framework[2], the Accountability Working Group (hereafter, “AWG”) designed a seminar that aimed to bring together diverse perspectives concerning sustainable development in connection to accountability. Prior to the seminar, the PhD Fellows in the Graduate School were challenged to provide a thoughtful, written reflection concerning accountability in the frame of sustainable development within their respective disciplines[3].

Most of the contributions centered on how the document Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (hereafter, “2030 Agenda”) or some of its Sustainable Development Goals (hereafter, “SDGs”) in particular foster accountability in the various disciplines represented in the Agenda 2030 Graduate School. Alternatively, how the 2030 Agenda questions the current accountability framework and urges stakeholders to make adaptations in existing accountability systems was considered as well. In this sense, some of the reflections addressed ‘SDG wrapping’ and ‘greenwashing’, or perhaps even worse, accountability policies that have little or nothing to do with the everyday reality in which they should be applied. Finally, one of the texts in the compendium focused on how accountability measures and approaches can help achieve a more sustainable society. Based on the contributions in the compendium, the AWG set up a seminar to discuss the topic in more depth.

Seminar framework

The AWG identified the conceptualization of accountability and the involved stakeholders as central themes in the compendium, and decided to base the seminar on these broad themes. The seminar was divided in three parts; a whole group exercise to expose the different perspectives and understandings; a sub group discussion to trigger sensemaking discussions; and a final individual reflection.

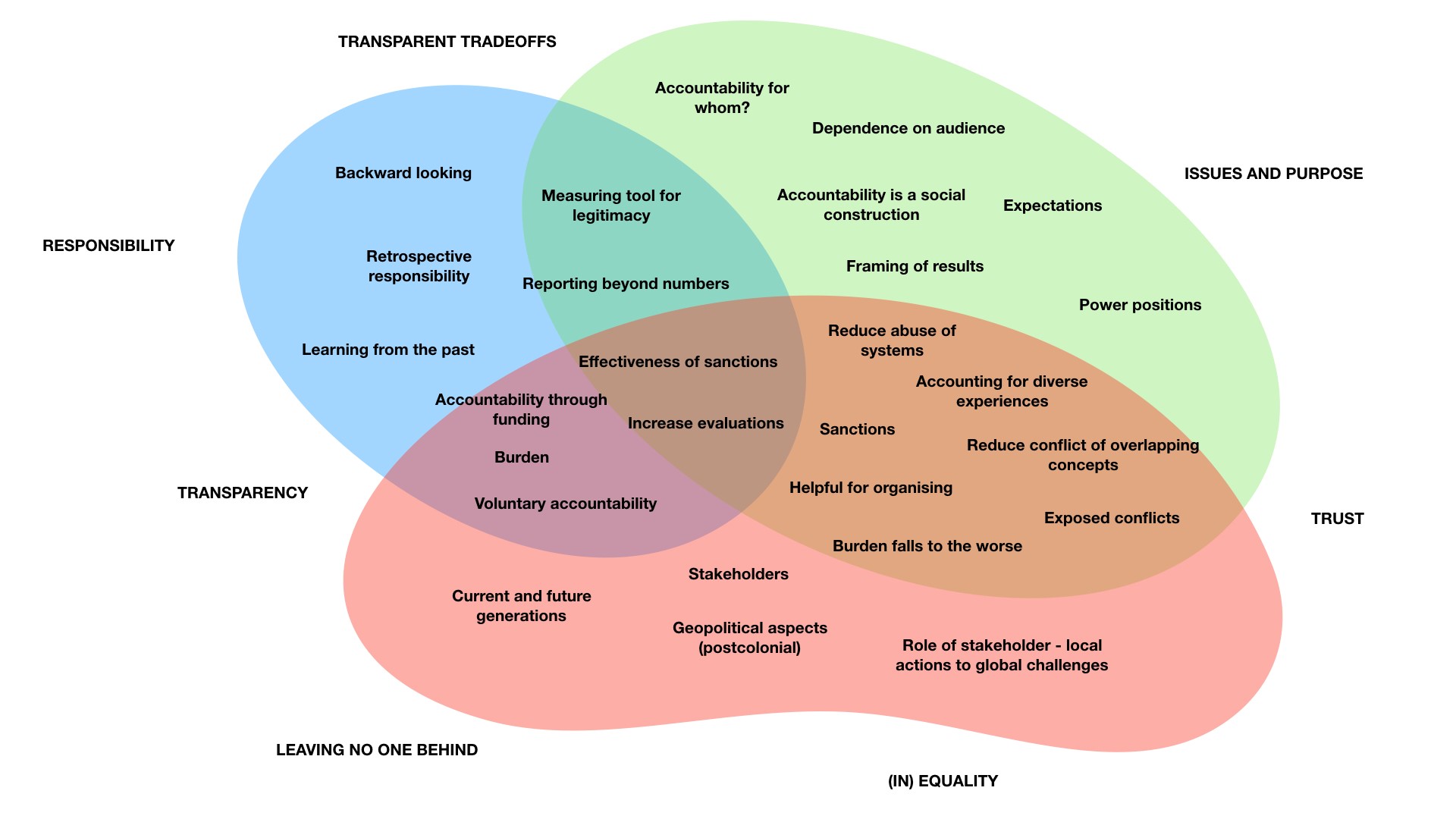

The first exercise of the online seminar consisted of a whole group conversation aiming to reflect on the different conceptualizations that participants had developed of accountability and sustainability. To identify the existing assumptions, participants were asked to summarize the main ideas of their texts, which were posted on a ‘digital whiteboard’. As a way of identifying connections between previously unrelated concepts, participants were instructed to express their ideas once they identified a potential relation with what was being discussed. This (somewhat) synthesis mechanism, enabled a rather organic recognition of patterns amongst the ideas developed by the group. In Appendix 1, it is possible to observe the result of this exercise. The aim of this exercise was not to obtain a unique or clear conceptualization of accountability and sustainability, but to shed some light on the diverse understandings and stimulate the cognitive skills of the participants. Organizational innovation researchers argue that the identification of shared and unshared features is helpful for creative thinking and that it might assist in developing more original and aspirational ideas[4].

After the first ideation exercise, the participants were divided into smaller groups to have more thoughtful discussions. The groups were invited to reflect on the following question: “What are the consequences of accountability in the context of sustainable development for stakeholders involved?”. Due to time constraints, the groups were only given 15 minutes to engage in this discussion. Afterwards, when reconvened, each group had the opportunity to share their findings with the other groups. The summaries of this discussion are presented in Appendix 2.

The last part of the event aimed to trigger individual reflexive and learning processes. Through an online survey conducted during the exercise, the participants were asked the following questions:

- “What did you learn from this activity (both the writing and discussion)?”

- “What were the challenges you faced during this activity (both the writing and discussion)?”

Even though the responses of all 12 participants vary widely[5], it is possible to conclude that the process did inspire some theoretical, practical, and/or personal reflections of the participants that, in turn, opened up a problematization and challenging of assumptions around the concept of accountability.

Concluding thoughts

The multidisciplinarity of the participants brought different perspectives around the concepts of accountability and sustainability. The combination of various fields of study and understandings enabled a unique aggregation of knowledge which can shed some light on the embedded assumptions within the represented fields. To formulate general conclusions from this exercise would, however, require a much more rigorous theoretical and empirical study. Nevertheless, developing solutions for complex endeavors as sustainable development, requires novel research approaches. Consequently, the results of this exercise have led to the identification and problematization of assumptions and concepts that can inspire research questions and increase the chance of developing breakthrough ideas.

Recurring observations on accountability in its practical application focused on burden-sharing, normative challenges and exogenous factors. The influences of tilted power balances were identified as problematizing the distribution of burden, where individuals shoulder more of that burden in proportion to their circumstances, namely at-risk populations and at a more macro level, the Global South. Numerous normative challenges were also identified as predating the mechanistic and instrumental applications of accountability, specifically questions of overlapping and conflicting concepts as well as historical tensions. Lastly, there exist certain exogenous factors afflicting accountability in practice, namely those of transparency in processes, concerns of trust and the effect of geopolitical tensions.

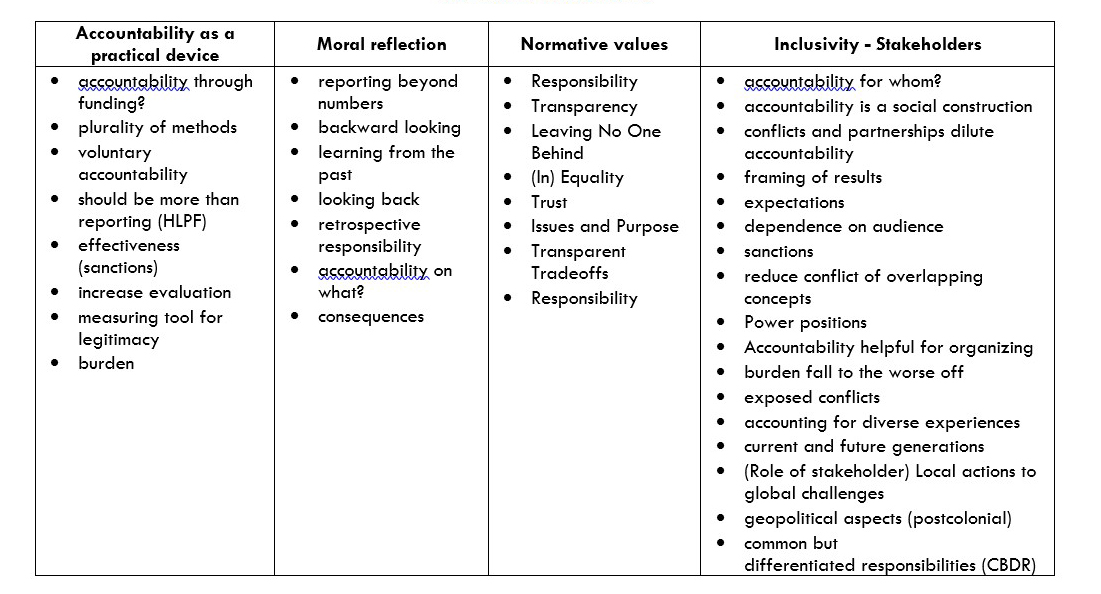

Acknowledging the theoretical limitations of the activity, there are, however, some points that are worth developing further. After reflecting over the patterns map, we identified the following connecting topics: (i) Accountability as a practical device; (ii) Moral reflection; (iii) Normative values; (iv) Inclusivity and Stakeholders. In Appendix 3 it is possible to see a categorization of the different patterns that emerged from the first exercise of the seminar. The idea of accountability as a practical device, seems to question the mechanisms and techniques that are designed to carry accountability exercises. The moral reflection category, points to the process of identifying and defining the objectives and obligations that should guide the accounting exercises, hopefully influenced by sustainability ideals. The normative values, are the minimum required principles or rules that should be present in any accountability exercise. Finally, the inclusivity and stakeholder component, highlights the importance of acknowledging the audiences and considering the power positions and the voices that are being silenced through the accountability discourses.

While no major conclusions can be drawn from this exercise, several questions were raised while reflecting and analyzing the ideas, discussions, and reflections that emerged from the seminar. It is important to clarify that the following questions assume an approach from a sustainability perspective:

Accountability as a practical device:

- How is the accountability in the context of sustainability being performed?

- What are the instruments that are being used?

- How are these instruments being designed and used?

- What are the limitations of the current instruments and how can we deal with them?

Moral reflection

- The interests around sustainability are context dependent, it is rather problematic to define a unique appreciation of what should organization be accountable for. Thus, how, in the field of sustainable development, should accountability practices by judged?

- What is the reflection process that organizations undertake when delimiting interests, the interests and objectives of their accountability process?

- How should organization reflect over their accountability practices in different contexts?

Normative values

- How are the normative values, as transparency, being performed in the accountability process?

- How can accountability systems facilitate and confirm the values inherent to the 2030 Agenda?

Inclusivity and Stakeholders

- How are the silenced voices in the accountability reports being highlighted?

- How is accountability considering the actors in less powerful positions?

- How are the different actors being empowered though accountability practices?

- How can accountability be more transparent?

- How can accountability systems be more participatory?

Overall, the Agenda 2030 Graduate School looks at accountability with critical eyes and raises some important concerns. Yet, despite its complex nature and the numerous questions it raises, accountability also holds a promising opportunity to evaluate efforts from the past and build on these evaluations to map out plausible pathways towards a sustainable future. The compendium and subsequent seminar have led to a variety of multi- and transdisciplinary outcomes that mirror the unique group composition and environment of the Agenda 2030 Graduate School. Acknowledging, however, the limitations in expertise in and experience with this challenging topic, and in search for opening the conversation beyond academia, it seems relevant to open up the discussion to different stakeholders and enabling more voices to be heard.

Appendices:

Appendix 1. Resulting patterns map from the exercise

Appendix 2. group discussion summaries

Accountability Consequences for Stakeholders:Group 1The idea that there is little to no consequences for stakeholders with power in terms of accountability. This represents a pessimism towards accountability and sustainability in general. The murder of George Floyd in the US shows that when an authority figure believes they can elude accountability, systemic consequences result. The question then is how do you respond to authority figures while pushing for a nonviolent approach to increasing accountability? The SDGs lack accountability in terms of advancing them, so states can sign onto anything but do almost nothing. Corporations are easier to hold accountable in the Global North, such as with Volkswagen and Dieselgate, but not as easy in the Global South. This means that transnational corporations can go into the Global South and get away with a lot without consequences. Reducing emissions in Sweden, for example, is understood in production but not in consumption. This means that consumption patterns continue to grow, but do not get accounted for in emission reduction goals. Holding states accountable is an overwhelming task. Group 2While there are three concerns about the SDGs, this does not call for pessimism. The formulation of the 17 SDGs influences accountability itself, though without expressly referring to accountability. However, since they are interconnected goals, whether that helps reaching accountability is a question. The second concern is the importance of political will and whether the SDGs are built towards accountability. In terms of urban planning, there are specific issues about how cities and the world should look. This grand overarching concepts are captured by the global political sphere, but they are also talking about different concepts. A third concern concern is that accountability is that it is limited to retroactive understanding. In contrast, urban planning, for example, looks at hundreds of years in the past and the future, which makes it an interesting topic to look at in relation to accountability. Group 3A pragmatic approach to accountability involves projects that are locally-based, but with SDGs embedded into them with a bottom-up approach. However, accountability can also be a burden against behaviour that lacks accountability. From the perspective of business, for example, accountability reporting can add to accountability. In the developing world, accountability is about counting money, impact, etc. It is more concrete and more action-oriented, using a lot of resources but often missing the point of what is being implemented. This is another sense of how accountability can impose a burden. In terms of accountability and power: who is accountable for what? Is it a relationship that is imposed? Development organisations may impose accountability on certain populations, but in a way that is not context appropriate. Accountability can then become a blanket instrument that is also a burden unless engaging in higher level concepts of accountability, such as those pertaining to human rights principles or encountering historical wrongdoings. Source: own elaboration based on socialization process |

Appendix 3. Pattern grouping

[1] Harvey, Sarah. “Creative Synthesis: Exploring the Process of Extraordinary Group Creativity.” Academy of Management Review, vol. 39, no. 3, 2014, pp. 324–343., doi:10.5465/amr.2012.0224

[2] Ibid, pg. 330

[3] The compendium of this reflection exercise can be found here.

[4] Ibid, pg. 330

[5] The responses can be accessed here.

[6] The original image of the whiteboard can be seen here

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any institution.