Posted on 30 April 2020 by Soo-hyun Lee and Juan Ocampo

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Agenda 2030 Graduate School or Lund University. The present document is being issued without formal editing.

The cross-cutting nature of the Agenda 2030 Graduate School at Lund University seeks to initiate collaboration, move the research front around societal challenges and profiling the university nationally and internationally as a significant player in the global sustainability work. In times of strain and isolation, this series seeks to open a frank and meaningful discussion on the need to not only persevere, but also advance the promise of sustainability.

This series is called: Times of Crisis. Over the last month, world structures were rattled by COVID-19. Adding to the regrettable loss of thousands of lives to the pandemic are the foreboding socioeconomic impacts that are becoming to come to light. To many, the economic impact brought by this pandemic overshadows the health crisis eclipsing humanity. Yet we must not forget that we live in a complex, intertwined world, where economic countermeasures cut across all aspects of life. The predominant shade of that complexity is a much older threat, perhaps one borne with the rise of human civilization: the irreversible need for sustainable development whose stark reminder comes in ever increasing scales of natural disasters – such as COVID-19.

In these entries we examine the sustainable development implications of COVID-19 economic countermeasures around the world to provide insight on how these efforts are moving in parallel or are working against one another.

From the earliest detections of COVID-19, governments around the world have been developing social and economic strategies in response to what would become one of the greatest challenges to healthcare systems known to date. Resilience is important in times of crisis, and observing how governments respond today becomes a point of departure for handling crisis in the future.

However, every country’s COVID-19 situation is different and so are their institutional capabilities and financial resources. Nevertheless, one of the main pledges of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is to “leave no one behind” and in this time of crisis it is important to keep this in mind. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) identified that people, or even countries, are being left behind “when they lack the choices and opportunities to participate in and benefit from development progress”. UNDP identifies the following five key factors in that effort: discrimination, geography, shock and fragility, socioeconomic status, and governance. COVID-19 is challenging each and every one of these dimensions. Reflecting on the structural differences between economies, this post presents two deeply divergent circumstances: Malawi and Canada.

The Case of Malawi

Malawi declared a state of emergency as a countermeasure to COVID-19 from the third week of March. The African nation has been implementing shutdown measures and the mobilization of national security forces to enforce them in ways now being seen in Malaysia, France, and the United States. Malawi set out an approximately 30mn USD Preparedness and Response Plan to help cope with COVID-19’s economic impact and development aid has been flowing into the country. With the help of the United Nations, the country hopes to initiate a social cash transfer programme that empower the most vulnerable populations prepare themselves against shock. However, there are bleak realities facing the least developed countries, LDCs, in the face of natural disasters and their economic fallouts.

The first is the state of health systems, which involves aspects such as governance, financing, delivery and access. The improvement of such systems in Malawi have primarily been on the supply-side: shortages in health workers, facilities and their geographical spread, particularly in rural areas. While Malawians have free access to healthcare for the treatment of major health concerns through the Essential Health Care Package, government expenditure on healthcare per capita is at less than 1/4th of prevalent benchmarks. The Malawi Health Workforce Observatory prepared under the auspices of the Malawi Ministry of Health identified that for every 41,045 people, there is one doctor – significantly lower than the 1:10,000 ratio set by the WHO for the achievement of UN SDG 3c. A COVID-19 outbreak would chip at each of these fragilities in the Malawian healthcare system, which puts particular emphasis on prevention.

The second is the role of economic migrants and international remittances. Working age populations in LDCs often migrate to countries where they may find greater opportunities for work, which in this case is South Africa. When migrant workers return from South Africa, while testing and quarantine are crucial, so is thinking about what happens to interrupted incomes. Migrants are not always on the receiving end of financial countermeasures devised by governments, meaning that indefinite pauses in employment like those we are seeing around the world, are that much more impactful against populations with little financial insulation against that kind of shock – particularly for members of shadow economies.

The third is interrupted supply chains and commodity market fluctuations. Tobacco leaf farming and export remain central aspects of Malawi’s economy at 11% of GDP and 60% of export revenues, but has been delayed due to the virus. Economic disruptions of this kind have lasting impacts, both in the shorter run such as being able to purchase vaccines, as well as in the long run such as ensuring children are able to have continued access to education after the shutdown of schools. This is particularly true in those areas most affected by a digital divide or where working age populations will have the prospects to work and for sustainable reintegration, both domestically and in foreign markets. These sectors are vulnerable to exogenous and commodity price shocks, resulting in vicious cycles powered by falling economic confidence. Such shocks were seen in the recent spat involving the US banning tobacco product from Malawi for the use of child labour.

The fourth is that rattled institutions face tests that are amplified by these extraordinary circumstances. In 2019, Malawi’s Constitutional Court overturned the results of the country’s presidential elections, fueling existing political conflicts with majority and opposition parties. Governance mechanisms are essential to ensuring that public financial and institutional resources are mobilized towards those areas of greatest need, such as testing and treatment, distribution of vital supplies and enforcing good faith government measures designed to counteract the spread of COVID-19.

Events like COVID-19 invariably have a much larger impact on LDCs like Malawi, where interrupting economic activity has much larger consequences in the face of structural or preexisting vulnerabilities. Responding to the earlier mentioned challenges are not unique to and therefore will not end with COVID-19. Systems will remain challenged, if not only by COVID-19, but also existing and continued gaps in progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Financial measures especially during times of crisis require accountability to ensure responses do not contradict one another, even if those measures may not explicitly be related to COVID-19.

The Case of Canada

COVID-19 doesn’t wait and governments must act accordingly. On January 25th, Canada confirmed its first case of COVID-19, however, by January 15th, the government had activated the Emergency Operation Centre to support Canada’s response. In March 17th, when around 400 cases had been identified, the government declared a state of emergency and was began developing specific regulations to tackle the crisis; one week later the total identified cases rose to 1,400 cases. Compared to countries in which there is not even the possibility to test the population or governments had fail to respond to the situation, it is possible to argue that Canada has acted promptly to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we must keep in mind that Canada is an OECD member with an estimated GDP per capita of 4,500USD, and a total health expenditure as a percentage of its GDP of 10%.

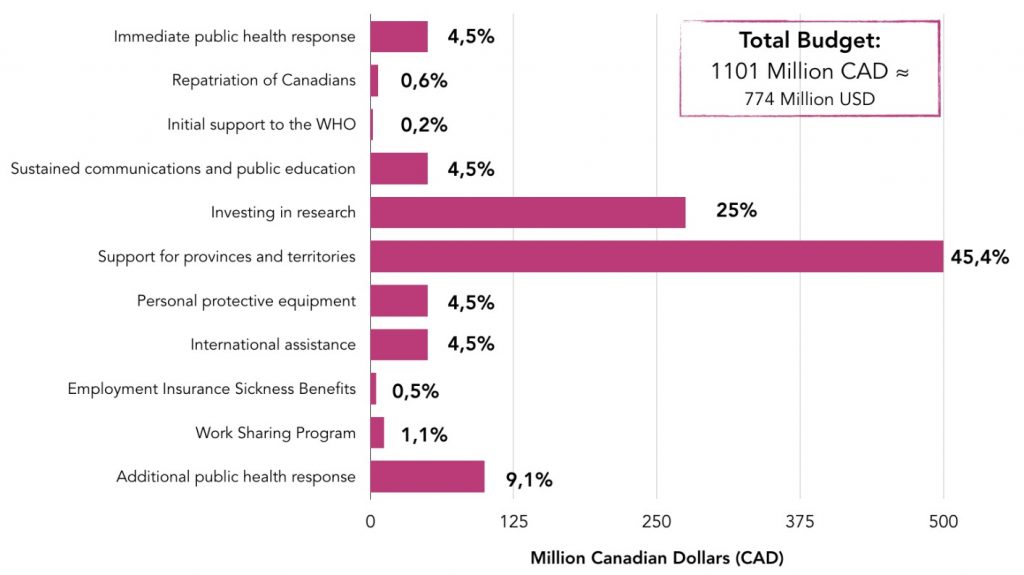

Based on the 2003 SARS experience, Canada prepared itself for future pandemics. The Canadian government has developed its strategy based on some guiding principles which are: collaboration, evidence-informed decision-making, proportionality, flexibility, a precautionary approach, use of established practices and systems, and ethical decision-making. Based on these principles, Canada aims to protect and inform its population, ensure economic resilience and collaborate with the rest of the world. By the 31st of March, Canada had invested 1101 Million CAD as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

Source: author´s projections based on data retrieved from canada.ca the 31st of March, 2020.

The Canadian government issued several social and economic regulations. Regulations in regard to mandatory self-isolation for travelers coming from abroad or people presenting symptoms have been put into place; however, by March 23rd, and even though the Prime Minister had advice people to stay home, there were still no mandatory quarantine measures. In regard to public gatherings, a guideline for “Risk-informed decision-making for mass gatherings during COVID-19 pandemic” was presented, however stating that each case is particular and never specifying a maximum amount of people. However, local governments have developed more strict measures in regard to this.

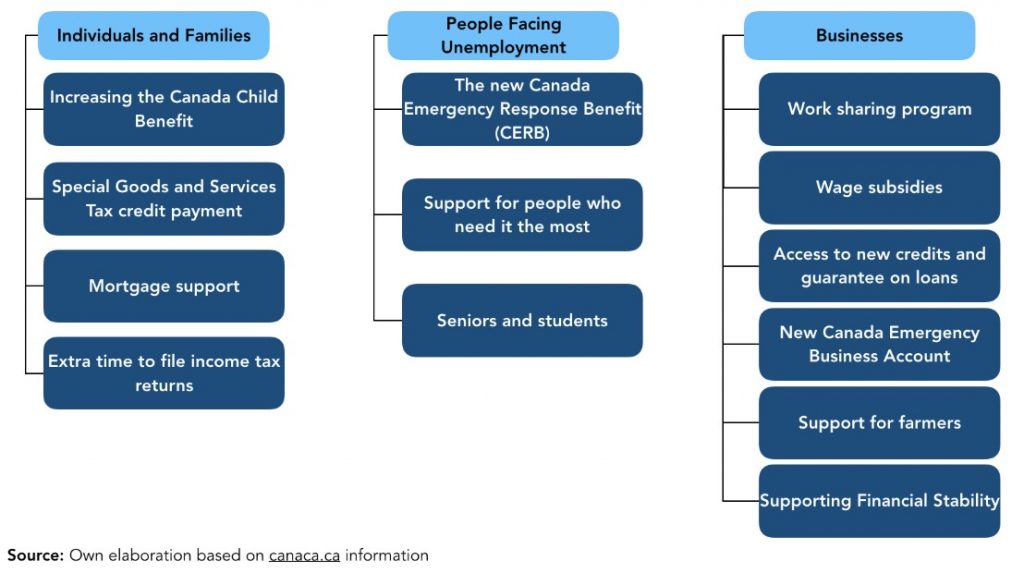

There are three main groups that have been targeted through several economic measures. Specifically, support for: individuals and families, people facing unemployment, and businesses. Each target group has specific and clear assistances that may include additional incomes, extension in mortgage payments, and access to credits and loans. For example, the work-sharing program which in times of organizational crisis provide benefits to the employees who organize and distribute available working hours amongst them, has been extended from 38 to 76 weeks. Figure 1 presents an overview of the different measures that have been put into place.

As measures for financial stability the government has developed four main benefits. First, the Canadian central bank has lowered the interests in an attempt to increase liquidity. Second, the government is buying uninsured mortgages to provide financial institutions with more liquidity, through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Third, the government has extended the time to pay and report income taxes. And, fourth the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) adjusts the Domestic Stability Buffer lowered the domestic stability buffer requirement from 2% to 1% for key banks. This requirement was supposed to increase to 2.25% level for the end of April, and is basically a measure to give confidence to markets and decrease the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. It is worth noting that this measure was set after 2008 financial crisis and aimed to assure that key banks had saved capital to work in times of crisis.

Every country has its own strategy to cope worth this pandemic crisis, however Canada offer several good practices that should be considered by other countries with less experience or capabilities. There are three main aspects that should be highlighted from how the Canadian governments seems to be handling the situation: (1) The information is complete and easy to access. In times of crisis having clear updates of the relevant information allows citizens to act accordingly and avoid the now common misinformation that travel through the social media. (2) Canada shows the benefits of digitalization in times of crisis. Having a digitalized administration facilitates the way people can interact with the government, apply to benefits and resolves its requirements, this gives confidence to the citizens and might calm citizens already with high level of anxiety. Finally, it is worth noting how the values that the government defined for times of crisis, seem embedded in the actions, packages and communications that the governments is developing. This shows coherence and coordination and should give a part of security to its citizens. For more information in regard to leading in crisis we recommend you the following article by McKinsey.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of any institution.