Posted on 19 February 2020 by Soo-hyun Lee

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Agenda 2030 Graduate School or Lund University. The present document is being issued without formal editing.

This article has been published with the Asian Development Bank Institute’s Asia Pathways.

The recent surge of interest in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investments has brought with it closer scrutiny of the way in which ESG factors are evaluated as conditions before an investment can be categorized as such. Environmental factors have been receiving a lion’s share of the attention in these investments, which have been riding on the institutional clout lent unto them by green growth. Governance factors, while not as much of a predominant issue for portfolio investments given their necessary acceptance of the domestic regulatory regime in which the investment is being made, also come with substantial institutional and academic presence, particularly due to the inclusion of rule of law in democratic peacebuilding. International financial institutions have also debuted enormous data-driven projects on governance factors, upon which they base their financing and risk decisions. Of these, social factors have by far been receiving the least (and most narrow) attention, largely due to the less obvious role that the private sector can assume outside of corporate social responsibility.

Private equity firms and financial institutions have been pouring considerable resources into boosting the coherence and profitability of ESG investments. However, rather than viewing E, S, and G as isolated variables, a co-beneficial approach is necessary in order to avoid the same problems that the progenitors of the World Bank governance indicators encountered. That is, an environmental factor viewed in isolation may have negative repercussions for the S or G factors. Systemic power imbalances, however, make this difficult to achieve.

Power relations is a common theme in the scholarship of environmental justice and degrowth. For instance, Akbulut et al. (2019) features a call for a “politico-metabolic reconfiguration” that views the use of ecosystem resources, the socioeconomic units that use them, and the institutions that govern both as constituting a single metabolic system. ESG, from this purview, offers enlightening options for reflection. Ecological and socioeconomic systems are seen as sharing a “continuous throughput of energy and materials in order to maintain their internal structure” over which “politico-institutional structure[s]” govern them in order to “reach higher levels of ecological sustainability” if seeking to achieve environmental justice. Viewing these ecological and socioeconomic systems separately means that their shared “throughput of energy and materials” shall no longer be aligned, tilting it off a sustainable balance. In understanding this balance, while a central consideration is the “power relations that shape metabolisms, i.e. the political economy”, there are other equally systemic imbalances that hinder the achievement of that sustainable balance that very much exist in responsible investment systems like ESG.

Bringing the social element of ESG under the lens of this discussion raises the challenges of how power relations affect the way that so-called socially responsible investments are screened or assessed across this scale of power relations. For instance, if the enactment of an environmental policy results in a more vulnerable social class shouldering a greater burden of the change, this moves only to deepen double injustices. The imbalance present in ESG to the E and G factors also provides a forum to reflect on this power imbalance challenge raised by the politico-metabolic configuration in an innovative way. That is, the imbalance between the power lent to environmental and governance factors in a nascent yet solidifying system of finance would, if left unaddressed, continue to subdue social concerns to the relative merits (accessibility) of environmental and governance factors. Within that scenario and in the operating principle of profit maximization, the potential social consequences of an ESG investment (or, perhaps, an E and/or G investment), may be considered to be acceptable collateral in the arithmetic of net value.

If one were to step back and view this challenge more metaphysically, then the entire undertaking of ESG investments and the reliance on indices can be ontologically problematic. Screening investments under a quantification of potentially competitive indices (such as socially responsible investment with lesser concern for the environment), can perpetuate the imbalance in power relations discussed in the metabolic purview. An investment that may be evaluated as partially sustainable or responsible due to its inclusion of environmental factors, as a less-contested regime, may promote unsettling social harm. As Martinez-Alier et al. (2012) identify with attempts to green gross domestic product, the extent to which various factors are included or excluded in these indices “reflect the social and political strength of different interests and social values” (Martinez-Alier, et al., 63). This challenge becomes especially reverberant when attempting to standardize those systems of indices across countries with highly disparate levels of development. If environmental factors are seen as the most accessible (in terms of quantification, for instance), then sustainable investment may harness investor confidence in environmental investments alone—even if those projects may very well exacerbate the power imbalances ingrained in social values, such as gender empowerment.

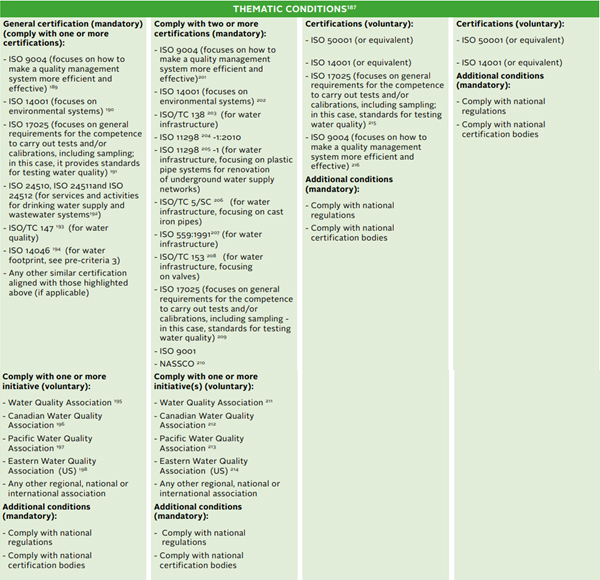

How are these power imbalances being addressed in ESG investments? One way has been by applying key performance indicators (KPI) that are different from entry condition requirements. For instance, according to the recommendations by the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) under its thematic investment category of water, companies that qualify for impact investments need to “generate at least 70% of their direct revenues from water products, services technologies or products” (or 100% for suppliers of crucial components or services) as well as satisfy the thematic conditions shown in Table 1.

Table 1: PRI Thematic Conditions for Water

Source: Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI). 2018. Impact Investing Market Map, pp. 56–57.

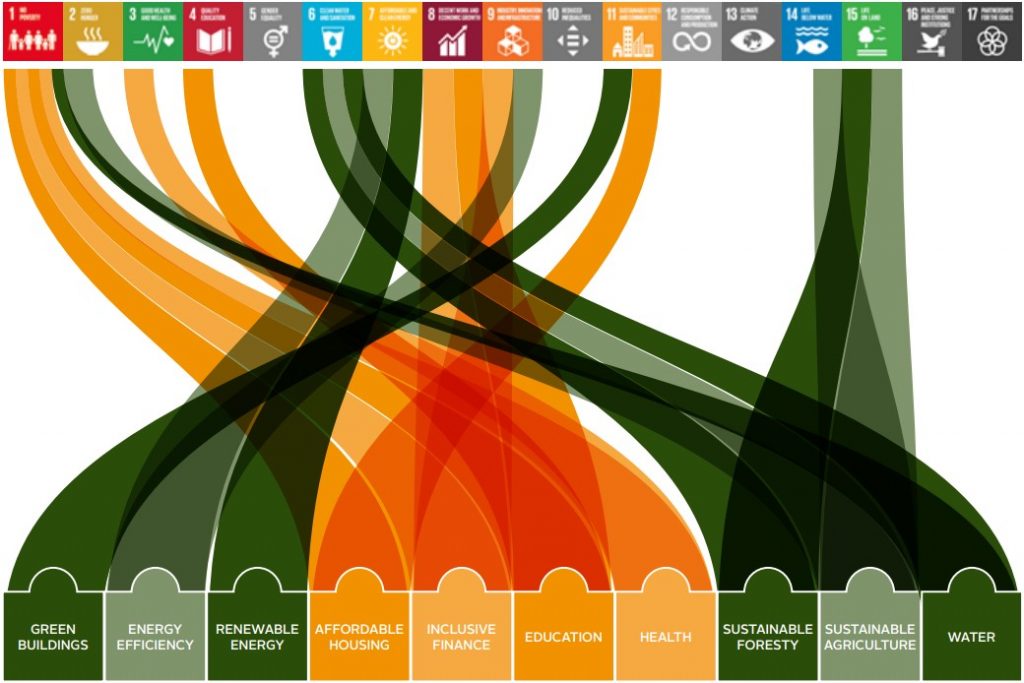

Simultaneously, common KPI used for thematic investments in water include such measurements as the number of unique women, unique poor individuals, and unique low income-individuals “who were clients of the organisation during the reporting period” (PRI 2018: 56–57). In reflecting on this approach, it becomes clear that embracing a metabolic approach to ESG investments depends on the rigour of the conditions imposed as well as the weight and design of the KPI. While investment in water and its impact within Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 are relatively easy to compute, this exercise becomes harder when working with topics such as SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). This is perhaps also reflected in the distribution of the representative thematic investments identified by the PRI.

Figure 1: Distribution of Thematic Investments Classifications by SDG

Source: Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI). 2018. Impact Investing Market Map, p. 99.

As responsible investment continues to grow, viewing the impact within the system of a continuous throughput shall without a doubt be a helpful exercise in addressing questions of power relations between stakeholders and stakeholding interests.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of any institution.