Updated on 18 January 2023, originally posted on 31 October 2022 by Alva Zalar (Department of Architecture and Built Environment).

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Agenda 2030 Graduate School or Lund University. The present document is being issued without formal editing.

The IPCC report of 2022[1] does not only continue to stress the absolute acute situation of the climate crisis, but also more clearly than its precursors move towards focusing on solutions. One of the key aspects of the solutions presented is greener cities, which is to be achieved by more sustainable and environmentally friendly planning[2]. The importance of green spaces is also demonstrated in SDG 11 Sustainable cities and communities, particularly in target 11.7[3] which demonstrates that green spaces are of both social and environmental concern. Simultaneously, in the last decades or so, notions of high-density residential space have emerged as the dominant feature in ongoing debates about ‘sustainable urbanism’, in particular in relation to how urban form might support mass transit infrastructure[4] and achieve social mixture[5]. Whether (the planning of) cities can be burdened with all that responsibility or not is another question, but what we do know is that there is a lot of hope to the promises of cities to achieve ‘sustainability’, not the least by being green and dense[6].

With this background, it is highly interesting to study the potential tension between two goals and values so clearly associated with ‘sustainable urban development’, namely, high density and access to green (public) space. In a recent article for City[7], we[8] attempted to study the effects on green space when a ‘compact city vision’ is pushed onto one of Sweden’s most infamous modernist residential areas: Rosengård. We studied the public planning documents connected to the Amiralsstaden[9] project, an urban renewal densification project aiming to improve the social sustainability in Rosengård, asking two main questions. How does the densification of the Rosengård area affect (public) green spaces? And how do the public planning documents discursively produce knowledge about the existing area and its green spaces, in order to realize this compact city vision?

Case study: the welfare landscapes of Rosengård

Rosengård was built primarily between 1963 and 1972 as a part of the Million Homes Program, and is located in the southeastern inner-city of Malmö, Sweden’s third largest city. Today, the area consists of a series of modernist neighborhoods and offer homes for just shy of 24 000 residents, primarily in multi-family housing units. Rosengård is the largest of Malmö’s post-war residential areas, and also one of the most clearly racialized as an ethnically othered place in Scandinavia. The area, along with many other similar neighborhoods, was receiving harsh criticism already from the early 1970s. The allegedly uniform and poor architecture and landscaping were associated with, and deemed to negatively affect, the residents[10]. The previous housing shortage turning into a surplus amplified the critique. Since then, both planning, design, community work, associations and other type of citizen-led initiatives has led to many efforts which deal with socio-spatial issues. The once-muddy fields between Rosengård’s building have in the last half-century systematically been recreated as lush green spaces, hosting a range of important recreational facilities and spaces.

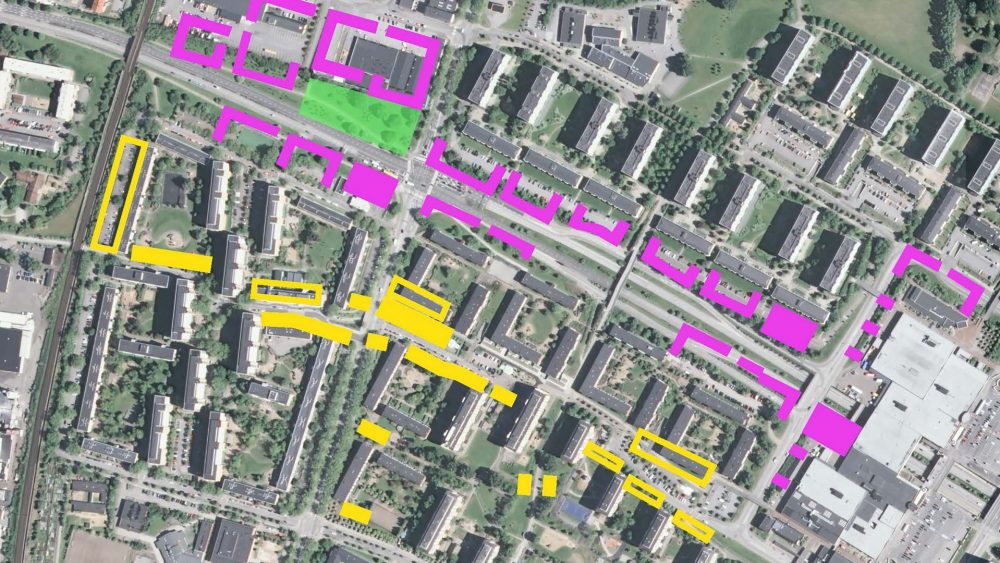

But the Amiralsstaden densification plans represents a clear shift from this gradual type of development in close relation to citizens, towards a large-scale development project. Studying the representation of green space and proposed densification in written documents, maps, photos shows that planners tasked with densification have adopted a new way of gauging space. While the potential for green spaces to become ‘intense’ and high-quality was consistently highlighted, the loss of green spaces and the increased pressure (through more intense use) was rarely even registered. Instead, the very existence (and, hence, qualities) of many green spaces were fundamentally obscured in public planning visions and strategies. The actual green spaces needed for renewal was thus ‘unmapped’ discursively, i.e., knowledge about particular spaces is actively obscured. Curiously, the Amiralsstaden project not only ‘unmaps’ existing green spaces by refusing to even acknowledge their existence in a systematic fashion, but then also selectively introduce these spaces back into plans as problematic features requiring planning interventions.

The hidden sustainability conflicts

By not recognizing the existing (modernist-type) green spaces of the area that is proposed to change, the densification can be rolled out without ever grappling with contradictory aspects of the plan’s green ambitions or necessary trade-offs. Densification seems to have become a sustainability fix[11], leading to an unsatisfactory account of the risks of sacrificing green space. Both the Amiralsstaden project and the 2018 comprehensive plan for the city of Malmö describes a vision of a ‘near, dense, green and mixed city’[12], but combining such values can be utterly contradictory and thus, the compact city is seldom ‘as green as promised’[13].

The ‘planning epistemology’ unmapping green space that we have identified in Rosengård leaves professionals with a pre-determined and narrow vision, hence, a narrow interpretation of sustainable planning. Furthermore, it underpins the dispossession of green spaces from the existing citizens in a clearly racialized, poor and stigmatized part of the city and undermines the planners’ discursive possibilities to engage productively with local demands to preserve green community assets. Green space is not only sacrificed, but the result is also affecting one the least politically influential communities. This is done despite the citizen dialogue of the Amiralsstaden project stressing the particular importance of local green spaces (courtyards) for women, elderly and children[14] – echoing the ambition of SDG 11.7 to ‘provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities’[15]. For green cities to be just, urban planning must to a much larger extent account for the everyday of existing spaces and residents in the areas that are up for ‘sustainable development’.

[1] IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press.

[2] IPCC climate report 2022 summary: The key findings https://climate.selectra.com/en/news/ipcc-report-2022

[3] https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11

[4] Bibri, S. E., J. Krogstie, and M. Kärrholm. 2020. “Compact City Planning and Development: Emerging Practices and Strategies for Achieving the Goals of Sustainability.” Developments in the Built Environment 4 (2020): 100021.

[5] McFarlane, C. 2016. “The Geographies of Urban Density: Topology, Politics and the City.” Progress in Human Geography 40 (5): 629–648.

[6] Angelo, H., & Wachsmuth, D. (2020). Why does everyone think cities can save the planet? Urban Studies, 57(11): 2201-2221.

[7] Zalar, A. and J. Pries. 2022. Unmapping green space: Discursive dispossession of the right to green space by a compact city planning. City 26(1): 51-73.

epistemology

[8] Alva Zalar from Agenda2030 graduate school and the department of Architecture and Built Environment at Lund University, together with colleague Johan Pries, associate senior lecturer at the Department of Human Geography at Lund University

[9] Malmö stad. 2015. Planprogram för Törnrosen och del av Örtagården i Rosengård i Malmö. Malmö: Stadsbyggnadskontoret; Malmö stad. 2020. Planprogram Amiralsgatan och Station Persborg: Från nu till år 2040. Malmö: Malmö stad.

[10] Hall, T., & Vidén, S. (2005). The Million Homes Programme: a review of the great Swedish planning project. Planning Perspectives, 20(3), 301-328.

[11] While, A., Jonas, A. E., & Gibbs, D. (2004). The environment and the entrepreneurial city: searching for the urban ‘sustainability fix’ in Manchester and Leeds. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(3), 549-569.

[12] Malmö stad. 2018a. Översiktsplan för Malmö: Planstrategi. Malmö: Malmö stad.

[13] Bibri, S. E., J. Krogstie, and M. Kärrholm. 2020. “Compact City Planning and Development: Emerging Practices and Strategies for Achieving the Goals of Sustainability.” Developments in the Built Environment 4 (2020): 100021.

[14] Malmö stad. 2015. Planprogram för Törnrosen och del av Örtagården i Rosengård i Malmö. Malmö: Stadsbyggnadskontoret.

[15] 11 Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11