Posted on 13 November 2019 by Soo-hyun Lee

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Agenda 2030 Graduate School or Lund University. The present document is being issued without formal editing.

Assessing whether a government measure or policy is legitimate in international economic law is largely contingent on inter alia the extent to which the measure or policy was able to exact its intended purpose and whether that purpose is determined to contribute to a matter of public interest. One significant factor in satisfying these conditions is good governance, which refers to government institutions as the progenitor of policy that seeks to maximize public goods. In that process, these institutions encounter a diverse range of public and private interests. Rothstein (2012) wrote that government institutions that are able to serve the “common good” as opposed to the interests of a select few at the expense of the whole is a central designation of good governance.

However, beyond this rather broad principle, attempts to codify a set of stylized assumptions on the common good have been profoundly unsuccessful. One such attempt was the Washington Consensus, which was built on the neoliberal assumption that economic growth would be the panacea for socioeconomic demands. The Washington Consensus aimed to maximize economic growth via “massive deregulation of markets, tightening of public spending, guarantees for property rights, and large-scale privatizations”. The failure of the Washington Consensus to deliver its projected outputs universally was in part due to the disparities in good governance. This meant that regardless of whether development policy may demonstrate a coherent internal logic, the absence of good governance in institutions would hamper the extent to which that policy can serve the common good.

Legitimacy provides a means to evaluate governance because it involves the sets of practices and norms that constitute the common good. Legitimate global governance would thus be a means to measure the extent to which governance institutions are responsive to the common good (or alternatively, the extent to which governance institutions need to be reformed). As Brasset and Tsingou (2012) show, the study of legitimacy becomes important in processes of transformation, like globalization, where fissures between private and public interests “spread across frontiers by market forces and by global trends”. One of the most pronounced demonstrations of this phenomenon is the environment and the irreversible changes that anthropogenic forces upon it. Legitimate governance must reflect changing and/or varying circumstances while keeping on course to advance the interests of the common good.

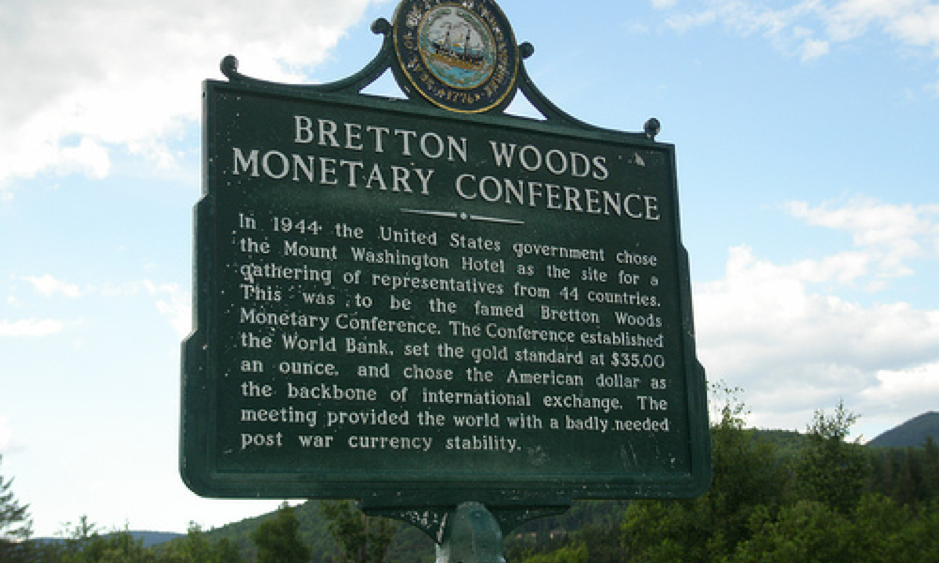

Returning to the Washington Consensus, one can then see that while it was an attempt to legitimize global economic governance under the rallying cry of neoliberalism, its operating principle was to converge diversities in economic, political and cultural modalities rather than acknowledge them. The Bretton Woods institutions that heralded this governance were charged with adapting initially noncompliant countries to a specific set of practices and norms that were given authority through their macroeconomic technicality. The success that industrialized economies enjoyed during the “golden age” of neoliberalism was the hubris behind such shock therapy economic and legal reform measures. The legitimacy behind these governance institutions were built on “engender[ed] rationalities” that defined “correct” or “normal” practices, much as one can see in financial markets and ratings agencies.

International economic law has largely been guilty of these same ontological fallacies. The legitimacy of government measures or policy is based on a set of practices or norms that seek to liberalize trade and investment. The instruments and mechanisms of international economic law, particularly dispute settlement, acts as legitimizing agents upholding those liberalizing practices and norms. Turning to the SDGs, it is evident that the legitimacy of trade governance is premised on differentiation (see, for instance, 3.b, 8.a, 10.a, and 14.6), which meant providing different treatment and compliance requirements based on the state of development. Turning to 17.10, however, clearly demonstrates that the normative substance behind the legitimacy is premised on set practices or norms:

17.10 Promote a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system under the World Trade Organization, including through the conclusion of negotiations under its Doha Development Agenda

Looking specifically at the WTO, it is clear that it has yet to work out the normative challenges concerning legitimacy as a governance institution. The collapse of the Doha Round of trade negotiations in 2005 and again in 2006 embody the division within the institution and its Member States on the constituent practices and norms of the WTO. During the Doha Round, the developing economy Member States of the WTO raised objections to full implementation of WTO obligations, seeking to carve out conditions that better serve their development context. These demands have run up against the desire of developed economy Member States, which largely seek to phase out the differentiated treatment offered to developing economies on the basis of freeriding and exploiting such entitlements in unfair ways. For instance, one such demand by developing economies has been to include special and differential treatment in enforcing compliance at the level of dispute settlement. While this would seem like a logical step in assisting developing economies reach their SDG targets, the legal ramifications of exceptional treatment to certain members are complicated. The WTO Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) and Appellate Body do not have the authority to set new standards or norms in the process of resolving disputes, rather they depend on enforcing WTO law. Yet without sufficient consideration of the normative issues concerning legitimacy that this exposition attempted to point out, the DSB and Appellate Body only serve as legitimization agents that perpetuate the existing normative shortcomings of the WTO as an economic governance institution.

There is no single, authoritative way to test whether a public policy, and at a wider scope governance, can claim legitimacy. The factors constituting legitimacy are inevitably intertwined with the theoretical foundations of a discipline as well as its practice and metamorphosis over time. Economic governance and its institutions, especially dispute settlement mechanisms like the WTO DSB and investor-State dispute settlement, must strive to engage this dynamic legitimacy or otherwise face the doldrums of institutional irrelevance.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of any institution.

Comments