Posted on 15 April 2020 by Maria Takman

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Agenda 2030 Graduate School or Lund University. The present document is being issued without formal editing.

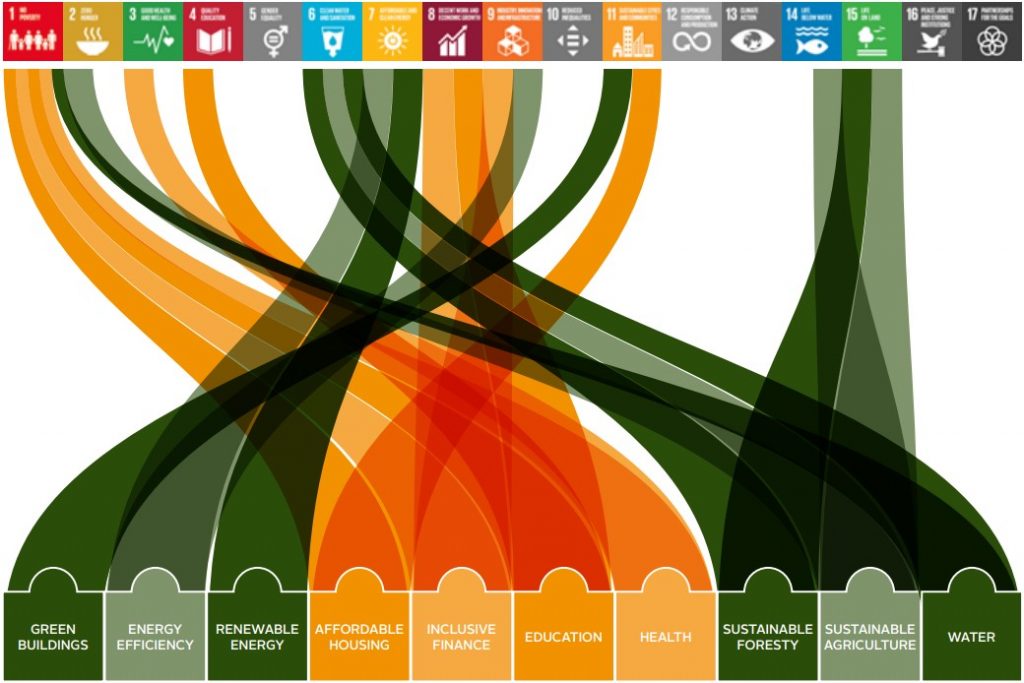

As long as humans have existed, we have used water for our living, which we through our bodies have turned into sanitary waste. The need to safely handle this waste and to protect the environment is expressed in the sustainable development goal 6, Clean water and sanitation (SDG 6). In many places, this is achieved through a system where we flush our toilets with water, and transport this water through large piping networks to centralized treatment plants, where the water is treated before being released into nature. Presently, the treatment processes are designed to remove organic matter and nutrients. However, an increased awareness of negative effects on the aquatic environment from other substances, such as pharmaceutical residues, has resulted in a discussion (both in Sweden and in the EU) about the need to develop our treatment plants further, to remove also these substances.

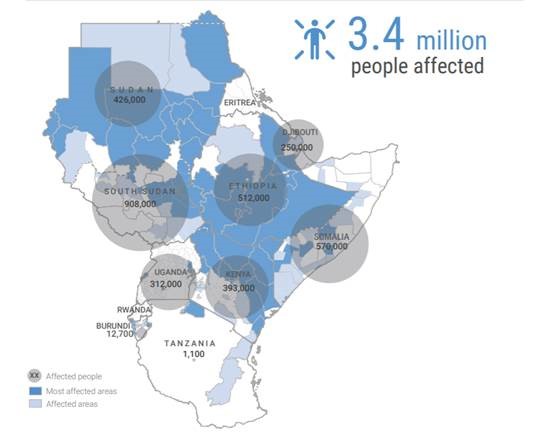

In the other end of the water cycle is the consumed freshwater, also included in SDG 6. Problems related to lack of water have existed in all times, but a changed water use, a growing population, higher living standards and climate change are factors that increase these issues globally and nationally in Sweden. Due to this, there is an increased interest to find alternative water sources in the future.

The two sections above, describing two different aspects of our water and wastewater system, are related. If we want to protect our aquatic environments from harmful substances, and at the same time need alternative water sources, there could be a common solution: to reuse our treated wastewater.

What are the challenges?

One could summarize the questions arisen on the subject of wastewater reuse as: where, what, how, and who:

- Where should the water be reused (drinking water, irrigation, industrial use)?

- What water quality do we need to reach?

- How should we treat the water in order to reach that water quality (treatment technologies)?

- Who is going to use the water, and what are their perceptions of wastewater reuse?

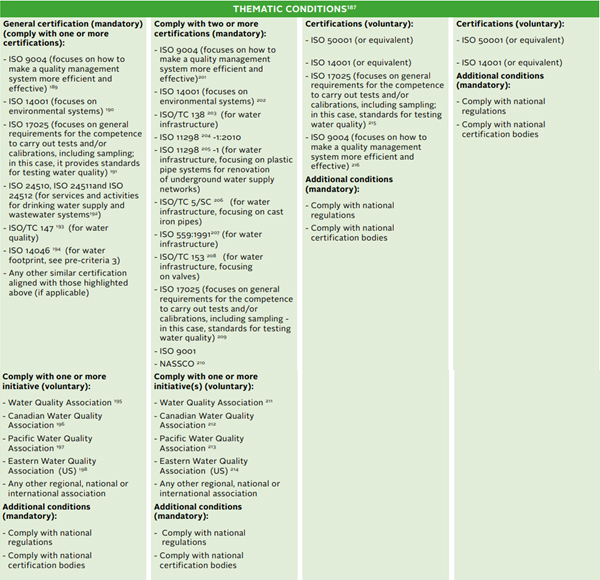

Regarding the “where” and “what”, the treated wastewater could potentially be used in many different applications, with different water quality requirements, such as drinking water, irrigation on farmland or in parks, or industrial use, to mention a few. In the European Union, there has been a proposal written for regulation of water reuse. It includes water reuse for agricultural irrigation and aquifer recharge, and proposes recommended restrictions on a few parameters, including some pathogens, organic matter and particles. However, a number of substances are not included, such as salts, pharmaceutical residues, hormones, biocides, or heavy metals. For drinking water production, the legislation in Sweden is however extensive, but pharmaceutical residues are not included today.

To answer the question “how”, there are many available technical solutions to treat the water to a very high purity, but potentially to a high economic cost. Possibly, both freshwater resources and legislation can affect how much a society is willing to pay for such solutions.

When the three first questions are answered, one of the most important aspects is still left to consider: who will use the water, and how can one gain the users’ acceptance. Wastewater reuse can be associated with big social concern, including impact on health, safety, and on the environment. This is not an easy issue, but transparency and communication are probably vital parts to gain peoples’ trust.

One should probably not think of these issues one at a time, but has to consider many aspects continuously along the way. In countries, such as Sweden, where wastewater reuse is not the common practice, it might seem controversial. However, globally it has been implemented for years, indirectly or directly, mainly due to lack of freshwater resources. The way it has been done can certainly provide inspiration and knowledge for countries where it is not the common practice, but where there might be a future need for alternative water sources. Reliable technical systems will be a necessity, but to achieve a successful implementation, also questions regarding legislation and social acceptance need to be considered and solved.

Comments